H. pylori Peptic Ulcer

H. pylori (Helicobacter Pylori) is a bacteria that lives in your digestive tract and causes peptic ulcers. Peptic ulcers are open sores on the stomach lining or the beginning of the small intestine (duodenum). H. pylori has adapted to the stomach’s powerful acids so that it can survive in the organ’s otherwise harsh environment. It typically infects children, and many people are unaware of an H. pylori infection because they have no symptoms.

What Causes H. pylori Infections?

Although the exact causes of H. pylori infections are still being researched, it is thought that they are spread by:

- Contact with saliva or other body fluids of an infected person.

- Contaminated utensils.

- Transfer of bacteria from the hands of someone who hasn’t washed their hands after a bowel movement.

- Contact with contaminated water or food.

Living conditions can also escalate the spread of H. pylori infections. These include:

- Lack of access to clean water.

- Living in an area with a poor sewage system.

- Living in crowded conditions.

- Living with others who have H. pylori.

How Does H. pylori Damage the Stomach?

H. pylori enters the stomach’s protective mucous layer. The bacteria is spiral-shaped, which enables it to tunnel into the stomach’s lining. H. pylori produces an enzyme called urease that transforms urea into ammonia, a substance that shields the bacteria from stomach acid. As H. pylori multiplies, this ammonia erodes the stomach’s tissue, causing a peptic ulcer.

It’s a common misconception that spicy foods cause peptic ulcers, but H. pylori is solely responsible for this condition. Spicy foods, as well as smoking, alcohol, and stress, can aggravate existing ulcer symptoms. Rarely do peptic ulcers lead to cancer.

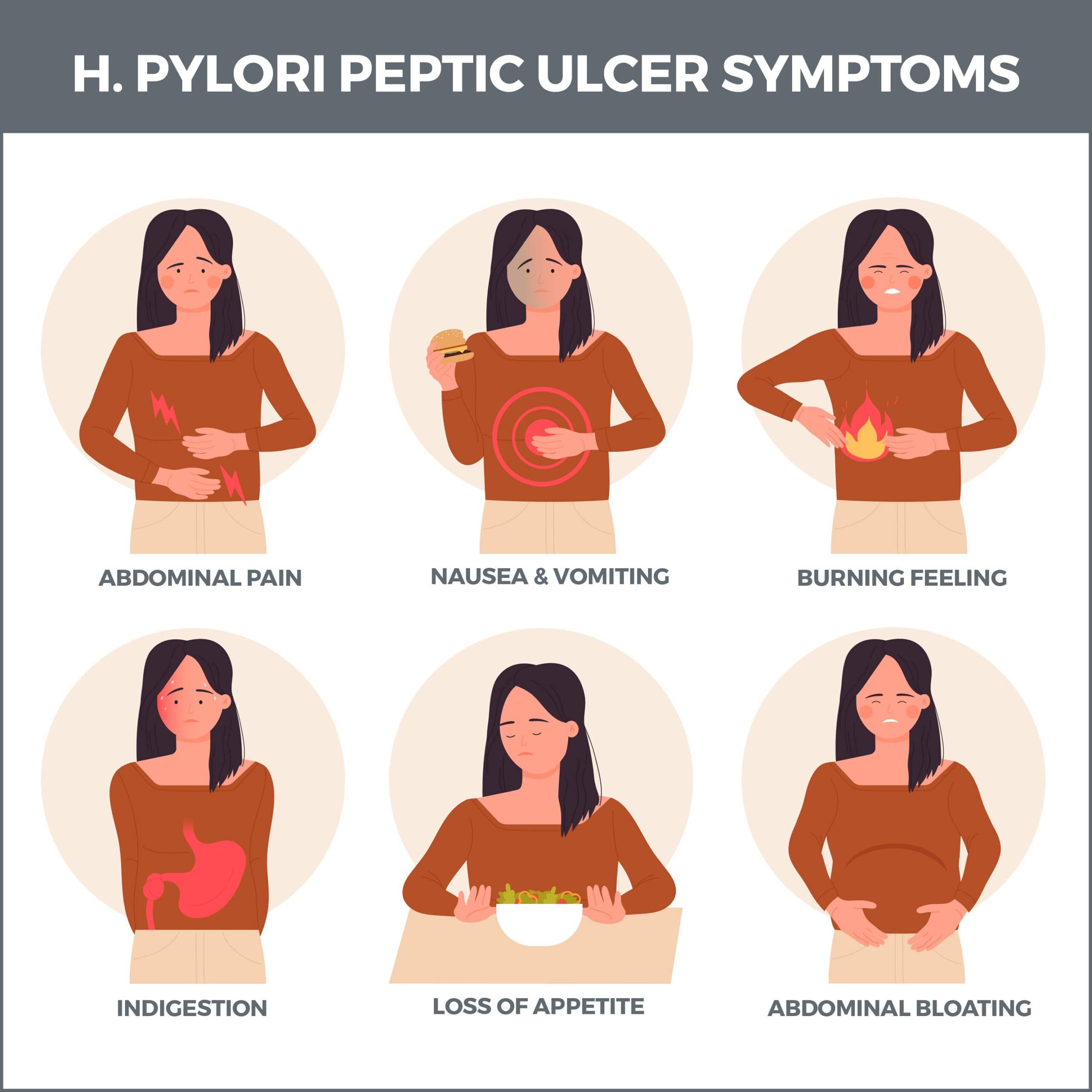

What Are the Symptoms of an H. pylori Infection?

Many people who have an H. pylori infection don’t know it because they don’t have symptoms.

If symptoms are present, they result from a peptic ulcer caused by the infection. These include:

- Bloating.

- Nausea.

- Burning stomach pain (usually several hours after a meal or at night).

- Unintentional weight loss.

- Indigestion.

- Loss of appetite.

- Frequent burping.

Ulcers can become dangerous if they bleed into your intestines or stomach. See your gastroenterologist immediately if you have any of these symptoms:

- Bloody, dark red, or black stools.

- Vomit that is bloody or looks like coffee grounds.

- Intense stomach pain.

- Unexplained tiredness.

- Difficulty breathing.

- Dizziness or fainting.

How is a H. pylori Infection Diagnosed?

One or more of these tests may be performed if it’s suspected that H. pylori bacteria is causing your peptic ulcer:

- Stool Test – there are two types of stool tests:

- Stool Antigen Test: This standard H. pylori test looks for antigens (proteins) in the stool that indicate an H. pylori infection.

- Stool PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) Test: This test can identify H. pylori infection in the stool, as well as antibiotic-resistant mutations.

- Blood Antibody Test: A blood antibody test analyzes whether your body has produced antibodies against H. pylori bacteria. Antibodies are proteins your body’s immune system makes when it senses a threat, such as bacteria. If these antibodies are present, it indicates that you have currently or previously had an H. pylori infection.

- Upper Endoscopy: A lighted tube with a camera is passed down your throat and into your stomach during an upper endoscopy. A small sample of its lining is collected to analyze for evidence of an H. pylori infection.

- Breath Test (urea breath test): A breath test is used to determine abnormal carbon dioxide levels, which could indicate an H. pylori infection. During this procedure, you’ll breathe into a bag before and after drinking a special solution containing urea. The test analyzes the amount of carbon dioxide in the bag before and after you drink the liquid. H. pylori is present if the carbon dioxide levels are higher after drinking the solution.

How is H. pylori Treated?

Standard treatment for H. pylori-related ulcers can take up to two weeks and is referred to as triple therapy. This is because it involves a combination of two antibiotics and one proton-pump inhibitor:

- Antibiotics: Antibiotics are taken to destroy bacteria. They include amoxicillin, Flagyl, tetracycline, Biaxin, and Tindamax. Two different antibiotics are prescribed to be taken together. This hinders the bacteria from building up a resistance to one antibiotic taken by itself.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Proton pump inhibitors suppress acid production in the stomach. These medications include Prevacid, Prilosec, Protonix, Aciphex, and Nexium.

Sometimes bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol, Kaopectate) is added to the combination of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors to coat the peptic ulcer and shield it from stomach acid.

Your doctor may also prescribe histamine blockers, also known as H-2 blockers. These medicines block chemicals called histamines, which stimulate the stomach to produce more acid. Histamine blockers include Tagamet, Pepcid, and Axid.

A newer medication called Talicia is a single capsule that contains two antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor.

If you’ve been diagnosed with H. pylori, don’t take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs). NSAIDs include aspirin, Advil, Aleve, and Celebrex. These drugs could increase the likelihood of developing an ulcer.

With treatment, most ulcers heal in several months.

How Will I Know That an H. pylori Infection is Healed?

Your doctor will perform a second stool or breath test several weeks after you begin proton pump therapy and antibiotic therapy.

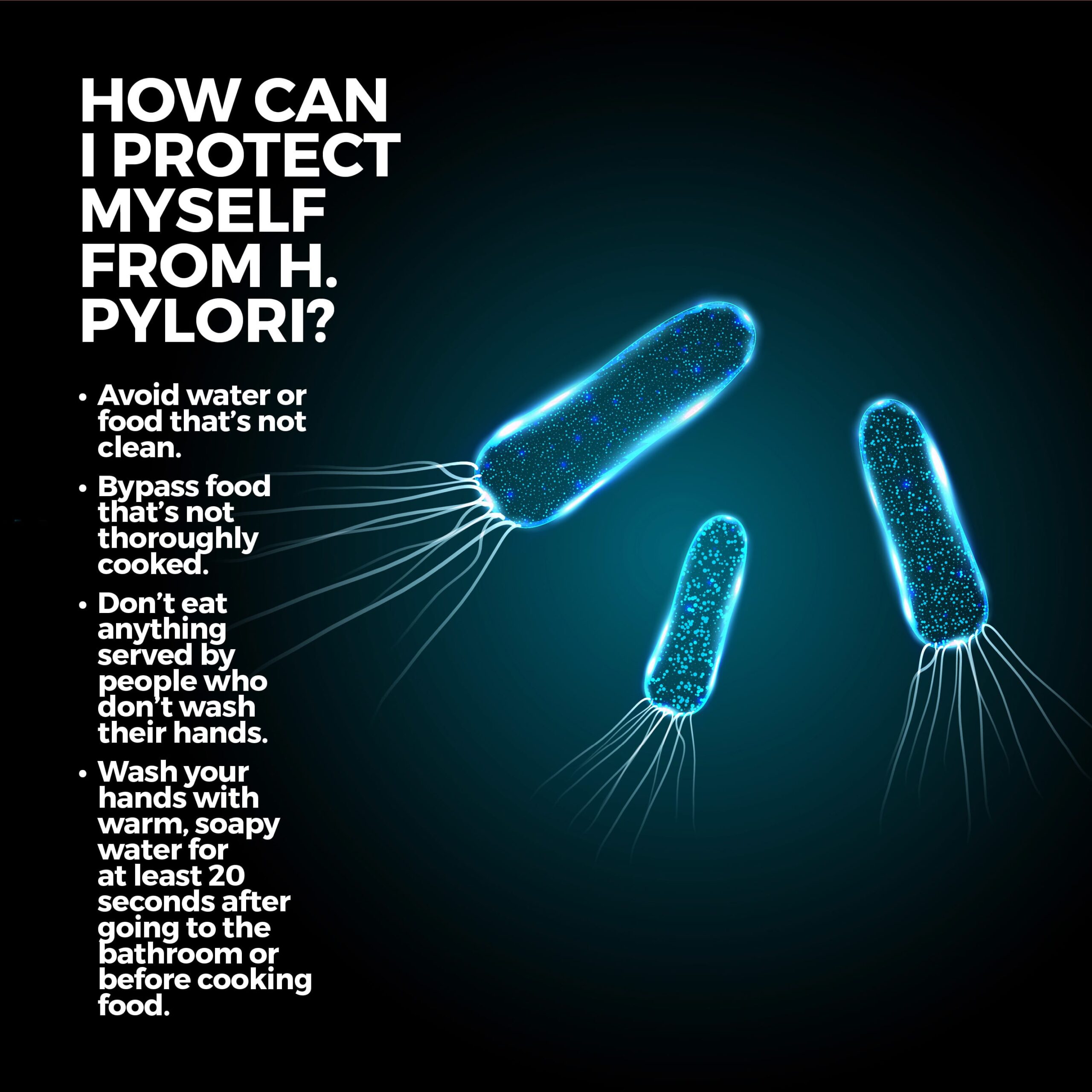

How Can I Protect Myself from H. pylori?

You can take these simple steps to prevent an H. pylori infection:

- Avoid water or food that’s not clean.

- Bypass food that’s not thoroughly cooked.

- Don’t eat anything served by people who don’t wash their hands.

- Wash your hands with warm, soapy water for at least 20 seconds after going to the bathroom or before cooking food.

What Are the Complications of an H. pylori Infection?

Although H. pylori can cause a peptic ulcer, the ulcer or Infection itself can trigger serious complications, including:

- Perforation: A perforated ulcer occurs when an ulcer burns through the stomach wall, allowing digestive juices to leak into the abdominal cavity. This is dangerous because it can cause a deadly infection called peritonitis. This Infection can rapidly spread through the blood (causing a serious condition called sepsis) and other organs, possibly leading to multiple organ failures.

- Internal Bleeding: Internal bleeding is the primary complication of peptic ulcers, and it occurs when an ulcer develops on a blood vessel. The bleeding can be gradual and long-term (leading to anemia) or fast and intense.

- Gastric Outlet Obstruction: Sometimes, a scarred or inflamed ulcer can block food from leaving your stomach. If inflammation is causing the obstruction, proton pump inhibitors or H2-blockers can diminish stomach acid levels until the swelling is reduced. If scar tissue has caused the blockage, surgery may be required. In other cases, this obstruction can be treated with a balloon endoscopy. This is a procedure that uses an endoscope fitted with a balloon that’s inflated to widen the blockage.

What Foods Should I Avoid if I Have a Peptic Ulcer?

Although foods don’t cause a peptic ulcer, some can irritate and cause discomfort. These include:

- Caffeinated and decaf coffee.

- Fatty foods.

- Citrus fruit.

- Chocolate.

- Tomatoes.

- Carbonated drinks.

- Nuts.

- Chips and other highly processed foods.

What Foods Can I Eat if I Have an Ulcer?

Certain foods are gentler to your stomach if you have an ulcer. These include:

- Low-fat and non-fat yogurt, cheese, cottage cheese, and milk.

- Whole grains.

- High-fiber foods.

- Lean meats.

- Fish.

- Smooth peanut butter.

- Sweet potatoes.

- Eggs.

Other Tips to Reduce Peptic Ulcer Symptoms

How you eat is just as important as what you eat. These habits could help reduce the pain of an ulcer:

- Sit upright throughout the day and while you’re eating. This goes for snacks too.

- Eat slowly.

- Thoroughly chew each bite.

- Eat five or six small meals throughout the day instead of three big ones.

- Relax before and after meals.

- Eat your last meal at least three hours before you go to bed.

Contact Us

Contact us today! The team of professionals at GastroMD looks forward to working with you. We are one of the leading gastroenterology practices in the Tampa Bay area. We perform various diagnostic procedures using state-of-the-art equipment in a friendly, comfortable, and inviting atmosphere where patient care is always a top priority!