Barrett’s Esophagus

If you have Barrett’s esophagus, the normal cells lining your food pipe (esophagus) change to abnormal cells resembling those in your intestine’s lining. This typically happens when your esophagus becomes damaged. The condition is incurable and affects approximately 30 million people in the United States, or 1.6%. Although uncommon, Barrett’s esophagus may raise your risk for esophageal cancer. This type of cancer is called esophageal adenocarcinoma.

What Causes Barrett’s Esophagus?

Barrett’s esophagus is a complication of gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). GERD is a chronic condition in which stomach acid backs up into your esophagus (acid reflux). People with GERD have a three to five times higher susceptibility to Barrett’s than those who don’t.

Usually, when you swallow liquid or food, a ring of muscle between the stomach and esophagus (lower esophageal sphincter) prevents the stomach’s contents from backing up into the esophagus. If you have GERD, this sphincter fails, causing food and stomach acid to leak back into the esophagus.

When this frequently happens for many years, it damages the esophagus’ lining, causing the formation of new, abnormal cells. Barrett’s can also be caused by swelling of the esophagus.

40% of people who develop esophageal cancer have never had heartburn. It is unclear why this happens.

Barrett’s isn’t genetic. It is called an acquired disorder, meaning it grows over time.

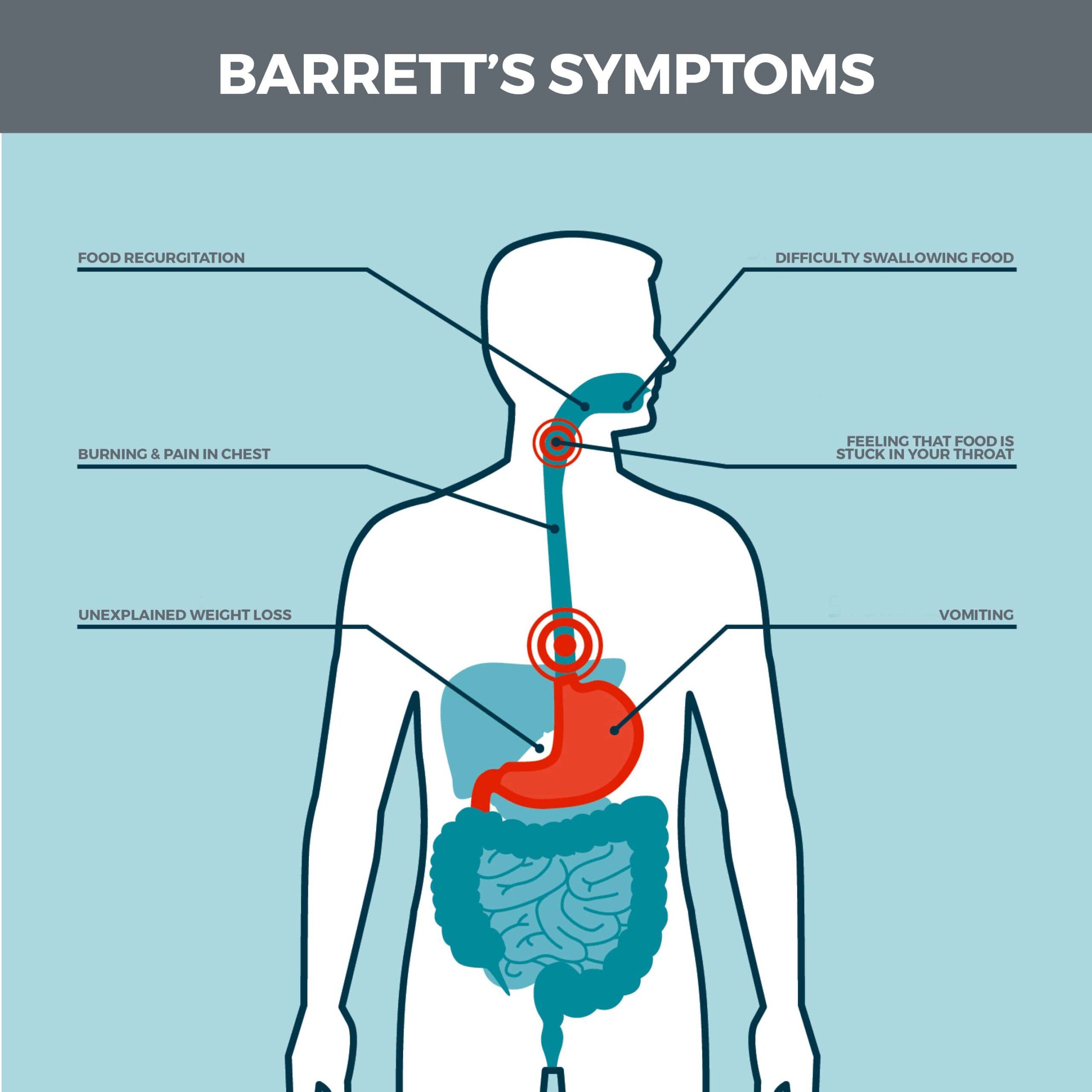

What Are the Symptoms of Barrett’s?

Some people with Barrett’s lack symptoms, while others have symptoms caused by GERD. These include:

- Difficulty swallowing food.

- Heartburn.

- Regurgitation.

- Feeling as though food is stuck in your throat.

- Constant sore throat.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Vomiting.

If you have Barrett’s esophagus, you will usually experience symptoms approximately one hour after eating. These symptoms can persist for hours after they begin.

Who is Susceptible to the Condition?

You have an increased risk for Barrett’s if you are:

- Male.

- Caucasian or Hispanic.

- Age 50 or older. Most people diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus have it ten or more years before it’s diagnosed.

- A current or previous smoker. Chewing tobacco is especially risky.

- From a family that has a history of the condition.

- Overweight, particularly if you have a lot of abdominal fat.

- Have chronic acid reflux and heartburn that doesn’t respond to medication.

- Have a hiatal hernia.

How is Barrett’s Diagnosed?

Barrett’s can be diagnosed via an endoscopy. During an endoscopy, a thin tube with an attached camera is passed through your mouth and into your esophagus. Your doctor uses the camera to examine your esophagus’ lining.

The endoscope is also equipped with tools for collecting small tissue samples. One biopsy is not representative of the condition of your entire esophagus, so your doctor collects biopsies every one-half to one inch of the affected part of your esophagus.

The cells will be examined in a lab to determine whether abnormal cells have overtaken normal cells. Normal esophagus tissue looks pale pink and smooth, while damaged tissue is salmon-colored and velvety.

If you’re having trouble swallowing, you may need an upper gastrointestinal (GI) barium test, also called a barium swallow. During the procedure, you’ll drink a liquid containing barium. This white contrast dye coats your esophagus, so it shows up more clearly on x-ray images.

How is the Extent of Damage Determined?

To determine the degree of damage, your esophageal tissue can be classified in one of three ways:

- No Dysplasia (abnormal cell growth): Damage is present, but there are no precancerous cells.

- Low-Grade Dysplasia: Cells show small indications of precancerous changes.

- High-Grade Dysplasia: Cells show many changes and are in the final stage before the cells become esophageal cancer. High-grade dysplasia sometimes regresses to low-grade dysplasia. Only one percent of people who have Barrett’s will develop cancer, but you should still have routine exams to detect early signs of the disease.

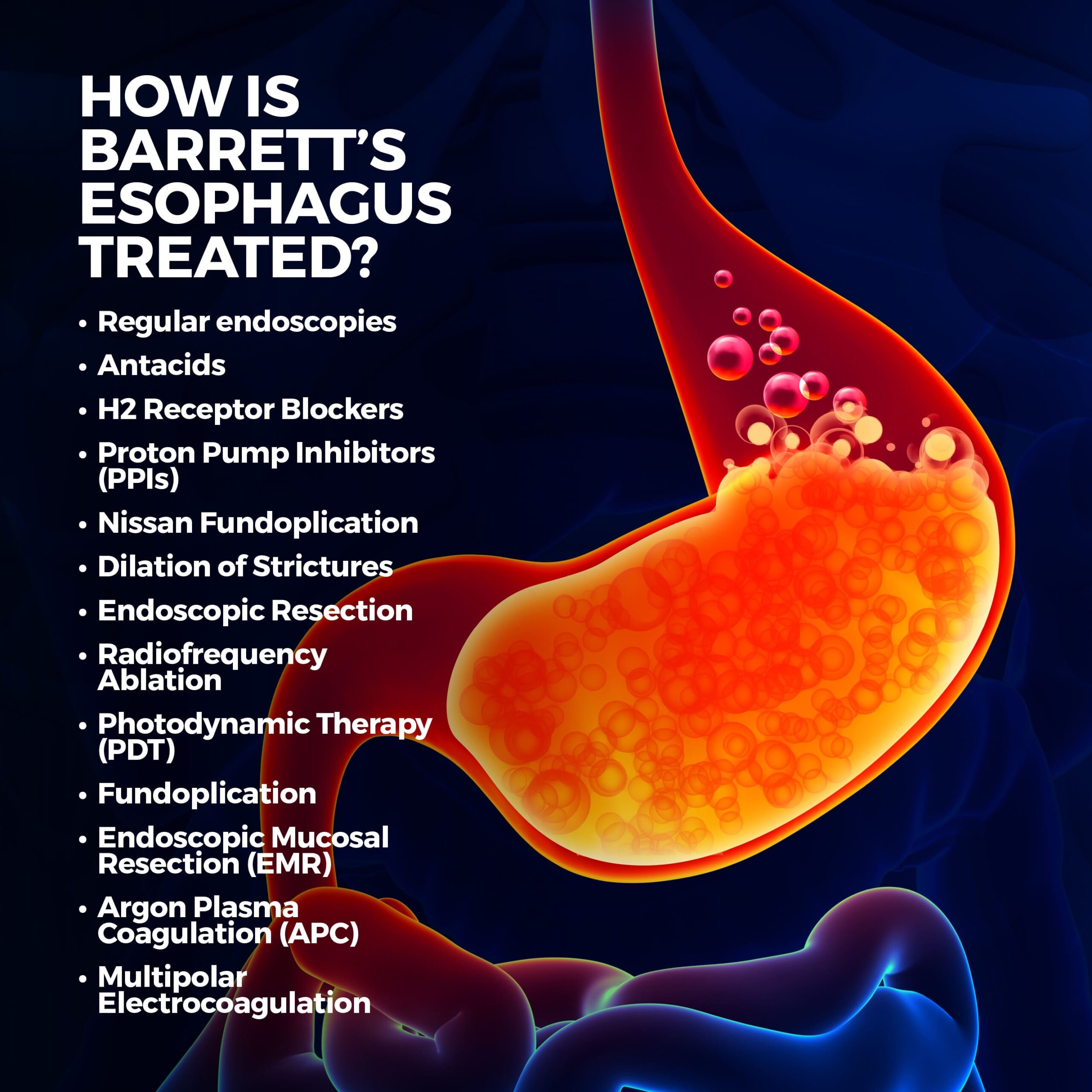

How is Barrett’s Esophagus Treated?

Barrett’s esophagus is uncommon, but you may need to be observed for it if you have heartburn or GERD. Treatment for the condition varies depending on the extent of abnormal cell growth and includes:

- Regular endoscopies: Getting regular endoscopies keeps track of your esophagus cells. This is used in cases where there is no dysplasia. If dysplasia isn’t present, you’ll need to get periodic endoscopies to ensure your condition hasn’t worsened. A follow-up endoscopy is usually performed in 12 months, and then follow-ups every three to five years.

- Antacids: Antacids are over-the-counter medications that neutralize stomach acid. They include Pepto-Bismol, Tums, Alka-Seltzer, and Mylanta.

- H2 Receptor Blockers (histamine blockers): H2 receptor blockers are medications that neutralize the acid in your stomach. They include over-the-counter treatments including Axid, Tagamet, and Pepcid.

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Protein pump inhibitors prevent acid from being released into the stomach. They do this by inhibiting specific cells in your stomach wall from “pumping” acid into it. When you take a PPI on an empty stomach, it triggers millions of these pumps, which the medication then turns off. These over-the-counter medications include Prilosec, Prevacid, and Nexium.

- Nissan Fundoplication: Nissan fundoplication is a surgical procedure that tightens the ring of muscle (sphincter) between your esophagus and your stomach. Usually, the sphincter opens and closes snugly when food passes through. When you have Barrett’s esophagus, it doesn’t close properly, allowing stomach contents to flow back into your esophagus. There are two types of Nissan fundoplication:

- Laparoscopic: this type uses small incisions resulting in faster recovery.

- Open Procedure: This procedure utilizes larger incisions so the doctor can insert larger tools and maneuver more easily.

- Dilation of Strictures (narrowed and thickened sections of the esophagus): If you have a narrowed esophagus, a special instrument gently stretches (dilates) the opening.

- Endoscopic Resection: During this procedure, an endoscope removes damaged cells.

- Radiofrequency Ablation (ablation refers to any procedure that cauterizes): This treatment employs an electrical current generated by radio waves, which heats and destroys abnormal tissue. Radiofrequency ablation may also be used after endoscopic resection.

- Photodynamic Therapy (PDT): Before this procedure, the patient takes a drug that makes cells light-sensitive. A laser fitted into an endoscope then kills abnormal cells in the esophagus without harming normal tissues.

- Fundoplication: Fundoplication is the surgical removal of the damaged section of your esophagus and attachment of the healthy rest to your stomach.

- Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR): During EMR, the abnormal lining is lifted, cut off the esophagus’ wall, and removed via an endoscope. EMR’s purpose is to remove cancerous or precancerous cells in the lining.

- Cryotherapy (cryoablation): Cryotherapy uses an endoscope to spray abnormal tissue with liquid nitrogen. This is similar to how dermatologists freeze off warts. Clear and colorless, liquid nitrogen has a temperature of -321 degrees Fahrenheit. Tissue cannot endure temperatures this cold. The cells are allowed to keep warming up and freezing, and this cycle destroys the abnormal cells. Over time, your body will naturally shed these cells. Other cryoablation techniques use a carbon dioxide spray, which is -70 degrees Fahrenheit, and a nitrous oxide balloon. Nitrous oxide is an extremely cold gas (-127 degrees Fahrenheit) used to freeze and destroy abnormal tissue.

- Argon Plasma Coagulation (APC): Argon plasma coagulation uses argon, a colorless, odorless, non-toxic gas, to destroy abnormal cells in the esophagus. A jet of gas and a spark are directed through the tip of an endoscope. The spark raises the gas to a very high temperature, burning the abnormal cells and coagulating them.

- Multipolar Electrocoagulation: Like argon plasma coagulation, multipolar electrocoagulation burns off damaged parts of the esophagus with instruments passed through an endoscope. This treatment can be used in tandem with a high-dose proton pump inhibitor.

Can Barrett’s Esophagus be Prevented?

You can reduce your risk of getting the condition if you:

- Eat lots of vegetables and fruits.

- Don’t eat large meals.

- Eat dinner at least three hours before bedtime.

- Eat slowly.

- Chew food thoroughly.

- Avoid bedtime snacks.

- Lose weight.

- Eliminate drinks and foods that cause heartburn, such as coffee, soda, fried food, greasy food, spices, onion, tomatoes, and alcohol.

- Reduce the use of NSAIDs and aspirin.

- Reduce consumption of saturated fats.

- Don’t smoke.

- Sleep with the head of your bed elevated. This discourages stomach acid from flowing back into your esophagus.

- Take medications with plenty of water.

- Stay active.

Contact Us

Contact us today! The team of professionals at GastroMD looks forward to working with you. We are one of the leading gastroenterology practices in the Tampa Bay area. We perform various diagnostic procedures using state-of-the-art equipment in a friendly, comfortable, and inviting atmosphere where patient care is always a top priority!